The Making of the Olympic Sundial

The construction of the 'silver sundial' in the Olympic Park has been a tiny cog in the huge machine that has now been working away since 2008 to build the Olympic Venues and Park on an area of largely contaminated land in East London But the sundial project has demonstrated in miniature the kind of cooperation between different companies offering different skills, expertise and experience that has characterised the way the enterprise as a whole has developed.

The silver sundial in the Olympic Park came about as a result of a competition launched by the Royal Horticultural Society in April 2009. Winners were amateur garden enthusiast Rachel Reid (21) and schoolgirl Hannah Clegg (12) who won the opportunity to work with the professional Olympic Garden designer Sarah Price to incorporate their ideas into a boomerang shaped site alongside one of the river tributaries which surround the Main Stadium, effectively making it a island, crossed by footbridges.

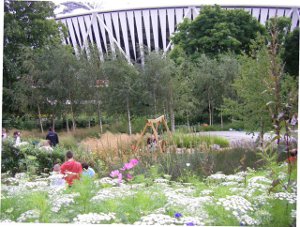

The Garden is known as the Great British Garden and one of the features to survive the development process was Hannah's Silver Sundial within the design concept of a garden featuring Olympic Gold, Silver and Bronze rings. The garden will offer elements of fun and discovery, with secret trails, a sandpit, a swing seat, a frog pond, the sundial and a stately oak tree with secret treasures of golden acorns.

Contractors appointed by the ODA to deliver the southern section of the Olympic Park included Arup Landscape, Skanska, and Willerby Landscapes within an overall design by LDA Design-Hargreave Associates. LDA Design, acting for the ODA, selected David as sundial specialist and supplier of the components on the project in November 2010. David began collaborating with Willerby's in March 2011. At a meeting in April, David learned the precise location of the sundial and the nature of the surrounding trees and buildings: David was concerned about the proximity and height of the main stadium and of nearby trees. Calculations suggested that there might be problem shadows from the stadium and the trees. The tallest MacDonald's building in the UK being built just across the way was thought unlikely to be a problem.

An analemmatic sundial is built flat on the ground, with 2 sets of hour points laid out around an ellipse (one for GMT and one for BST). The user stands on a date scale in the centre of the dial which shows the correct place to stand throughout the year. Additional markers explain how to use the sundial, also where and at what time the sun rises and sets. As this was to be a 'silver sundial', it was decided that the hour points and instruction plates should be made of stainless steel.

This sundial - like all others - had to be designed for the latitude and longitude of the site and orientated correctly. ln this case, the Prime Meridian ( 0 degrees ) passes almost directly through the Olympic Park, originating as it does at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, approximately 4 miles to the south. Nevertheless, a true north/south line is needed at the site for getting the orientation of the dial correct.

David visited the Olympic Park in June 2011 to establish this north south line and lay out the correct positions for all the components with the Willerby's team. An interesting divergence of readings emerged between the high tech satnav method of the Skanska surveyors (with the sensor maybe wobbling around a bit on top of its pole) and David's low tech method using a board, set square, pencil and the shadow cast by the sun. The discrepancy would have meant a difference in time of 15 minutes on the finished dial. An amicable discussion followed and it was decided to go with the sun reading - after all it was to be a sundial ! But you can be sure that David double checked all the calculations he had based on his reading when he got home. He also took azimuth readings on site in order to calculate wether or not there would be a clear path through the trees and over the stadium for the sun to shine on the dial. He concluded that in spite of many existing trees to the north, east and south east of the site, the dial would be sufficiently open to the sun during the Olympics for the dial to be viable. The oak tree in the gold zone of the garden is not a great problem at the moment but will become increasingly so.

Meanwhile the components had to be sourced, manufactured and delivered. David prepared the technical drawings and commissioned a fine piece of monumental quality welsh blue-black slate from Welsh Slate at Penrhyn for the central date scale of the dial. Stainless steel to form the markings on the date scale was bonded into the slate by Aquacut at Knutsford. Meanwhile, at the other end of the country, in Lyme Regis, Dorset, discs and rectangles were being cut from 5mm stainless steet by Precision Waterjet Ltd. Holes for the countersinks were drilled by Fisher and Co of Somerton. The stainless steel components were polished and etched black by Galsworthy Graphics of Wick near Bath. In the event, a problem emerged with the black enamelling, so the plates were cleaned of the enamel to leave a matt internal finish, and repolished to provide the maximum possible contrast between the background and the etched letters and numerals.

Installation of the sundial was completed in January 2012. Situated between the main stadium and the World Square, it will come alive during the games and subsequently, when visitors to the Great British Garden will pass through the gold, silver and bronze 'rings' and experience the colour, fun and discovery which was built into the original vision and realised through the contribution of just some of the vast number of Olympic contractors.