Making His Mark

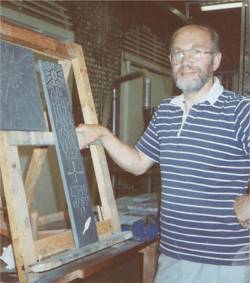

Anne Simon meets David Brown, Diallist

Dialling is the ancient art - and science - of making sundials, and David Brown is one of its modern exponents.

David, who retired from teaching last year, always has two or three sundials on the go. Up and about too early to disturb neighbours with hammer and chisel, his day might start at the drawing board working on a new design; later, as paint dries on a dial in the workshop, David sits upstairs at the computer, calculating the precise positions for the hour lines on the face of yet another job.

At other times he may be cutting a gnomon from a sheet of brass, shaping stone in the garden, researching ideas, quotations or illustrations, driving to Wales to select slate from the quarry.

When I visit, David is putting the finishing touches to a dial commissioned by the University of the Third Age at Salisbury, to be installed in St Thomas' Square to commemorate the Millennium. Also in his workshop are a small gravestone for a client's favorite cat, a horizontal dial for a 60th birthday present and a decorated house nameplate, all in slate.

I notice 'DON'T PANIC' amongst the incomplete fragments - testimony to an ongoing apprenticeship in letter cutting.

Outside, neat piles of cut Portland stone are stacked up ready to be turned into the kind of sundial that is laid out on the ground - an analemmatic dial - for Eastleigh Borough Council; and all around the (small) garden stand pieces of slate and stone, some carved, some waiting to be used, some obviously relics of past efforts.

I imagine David to have been one of those dedicated teachers you could never imagine retiring. Yet his energy and enthusiasm have long encompassed sailing, navigation, astronomy, music, the occasional major project in house or garden, even ritual toffee making at the end of every term; a veritable polymath, in fact, and everything tackled with skill, determination, diligence and a meticulous attention to detail.

These latter qualities were perhaps born out of a family background where David, one of four children of a Methodist manse, had every opportunity to follow a scholarly father, but also as a matter of course shared household duties with their mother in the days when sweeping the chimney was an annual chore and learning to drive could be done unsupervised during the Suez petrol shortage

It is the unique combination of science, art, history and craftsmanship that makes dialling such a perfect outlet for David's skills and interests. ' It's amazing,' he says, 'that I can combine all these things in one creative activity and end up with something that is practical as well as artistic and interesting.'

David studied aeronautical engineering at Imperial College, London, then trained as a teacher of maths and physics. Calligraphy, heraldry and woodwork had been pursued as hobbies at boarding school. But not until he attended a course in letter cutting in slate and stone at West Dean College in 1990 under Tom Perkins did he get hooked on the technique that is now at the heart of his sundial enterprise.

Several practice lettercut pieces later, and after a chance encounter with professional stonemason John Williams, then making a spectacular dial for Dean Close School in Cheltenham, David was making sundials of his own. He joined the British Sundial Society which was founded at about that time. Since then he has pursued letter cutting in slate or stone, specifically in the making of sundials, as his principal hobby. (Glass engraving is a recent development.) Now he is turning his hobby into a small business.

I browse through David's overflowing portfolio which is stuffed with photos, drawings and press cuttings - David is proud of the fact that he has made dials for prestigious locations such as Penshurst Place in Kent, the National Trust in Somerset and Darwin College, Canterbury as well as Kingswood School in Bath where he worked.

But getting just the right design for, say, the narrow high garden walls of a charming nineteenth century Bristol townhouse, or the sweeping lawns of a chalk downland garden in Buckinghamshire - two upcoming projects - is equally satisfying. And the science for each sundial is unique, according to its latitude and longitude.

David's sundials range in size from dolls' house to playground dimensions, and he makes all types of dials.

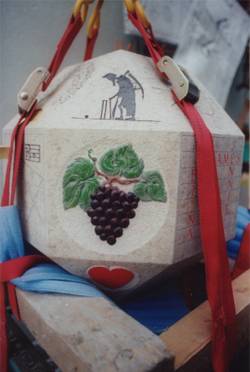

Whilst I think the most beautiful is an absolutely plain dial carved straight on to the pediment of a prizewinning classical gazebo in Bath, his trade-mark is probably the highly decorated multifaceted polyhedral sundial of the kind beloved of renaissance diallists.

Nowadays these are usually made as very special birthday gifts, typically having about twenty faces, six or more being sundials, all the others carrying painted and gilded carvings relevant to the recipient's life and interests.

This was the kind of dial he designed for a competition to make a sundial for the Pocock Garden at Christ Church, Oxford and his was the winning entry. Here the historical aspect was very important, for David researched the site where the dial was to be installed and came up with a design based on a dial created in the sixteenth century by the famous mathematician and horologist Nicholas Kratzer.

I wonder whether David misses teaching - not a bit, he says. But the familiar front of class stance is occasionally pressed into service as, for example, impromptu conductor of the Radstock and Midsomer Norton Silver Band where his normal position is amongst the tuba players. I also hear that he once close questioned a group of Florentine road menders ( in non- existent Italian ) to discover what stone they were using and where it came from !

Nearer home, I'm reliably informed that, for his three sons- in-law, trial by helping to install sundials has definitely replaced trial by sailing as mate to David's skipper as an essential part of the family tradition!

As for his new lifestyle: 'I love it! And I like the fact that when I go up to Shipham for meetings of the Mendip Calligraphy group, I'm quite near the old Somerset Schools Observatory at Charterhouse where I used to take groups of schoolchildren to stargaze years ago when I taught in West Somerset.'

As I leave, David returns to the Salisbury U3A dial to scratch his mark at the base. It has always been the custom for stonemasons to carve their own particular mark on each piece of work. David is proud to continue this tradition and be counted among their number. I left with the feeling that David is indeed making his mark!

Originally published in The Mendip, Bath & Northern Somerset magazine, Issue 8 Winter 2000. Reproduced by kind permission of Halsgrove Magazines